By Rural Builder Staff

Not many youths know what they want to do when they finish high school, but Jonathan Ota knew. He wanted to go into the military. His Dad was a Marine and he admired him. Further, his experience in school made him feel sure that he didn’t want to go to college. He had pumped gas, worked in the supermarket, and roofed houses and none of those jobs tripped his trigger. Of course, he says that roofing was different back in the day. “You didn’t have fancy lifts to move the roofing material up to the roof; it was all on your shoulder as you went up the ladder.”

Ota entered the military when he finished high school. Initially he loved it. He enlisted before 9/11, but he was deployed three times in four years and by the time he was done; he was suffering from PTSD.

After his release, he tried various jobs, including working at a mortgage company and managing a construction company. The construction company felt uninspiring; the owner needed things completed quickly so speed was the focus. This didn’t sit well with Ota; he was an ambitious person and he wanted to do things well and feel pride of craftsmanship.

Ota signed up for night school at North Bennett Street School, a trade school; he wanted to learn his craft so he was able to provide the kind of quality he envisioned.

He found that he enjoyed carpentry and learned to make furniture. But more importantly, he found his community. Ota said, “At the trade school everyone was happy. There was a sense of camaraderie I hadn’t experienced since my time in the military.”

One of the wonderful things about the sense of community is that it was among a group of people who were quite diverse; gender, age, and ethnicity played no part in it. It was just a bunch of people who loved working with their hands. Some of the people you wouldn’t expect would be into this you’d find out were creating the finest work of all.

His instructor saw promise in Ota and suggested he apply for the mikeroweWORKS scholarship. Winning was a huge help since he was in his mid-thirties with a wife and kids at that point. He managed to save some of the money for equipment, and when Ota graduated he opened his own shop.

The camaraderie continued as four of the graduates got together and opened four businesses in a building that one of the students had inherited. It works well, Ota says. They each have their own corner and they share the larger machinery among them, thereby making it more affordable for all of them.

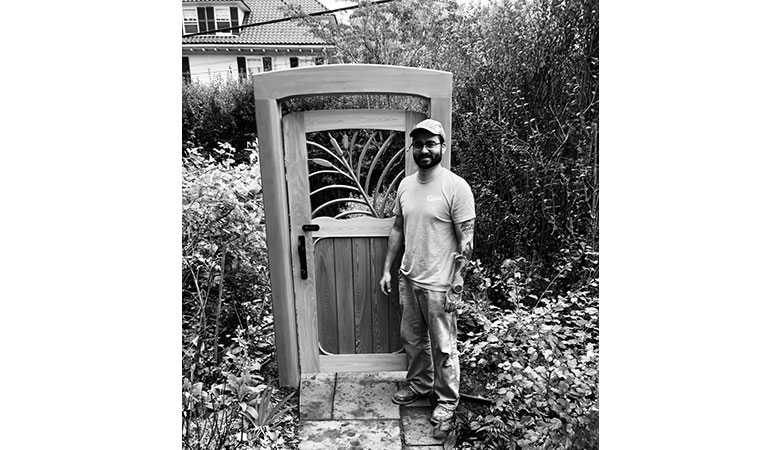

Ota’s business is called Gunner Grey Furniture Fusion. “Fusion” refers to the well-balanced design and clean lines from Japanese culture that he incorporates into his work. It’s particularly satisfying to Ota as it is a bit of his own heritage that he taps into.

Ota finds his work amazing; working with his hands as he does seems to be therapeutic to him, and the PTSD is pretty well controlled now. Working with power tools keeps his mind razor sharp, and the sense of peace flows over into the rest of his life.

Part of what he loves about his work is planing down into wood to see the grain. He feels bad that a tree was taken down, but by turning it into a work of art, it is like he’s “bringing nature back to life.”

Some of his favorite work is special projects, such as display cases, reception desks, and kitchen cabinets. He is working on a big bookcase that has a Norwegian flair. Norwegian style with carved dragons and hidden compartments speaks to him.

Ota says that a person can make a very good living making custom furniture. He says, “The sky’s the limit if you like the work and have the ambition and skill. He has pretty lofty goals himself. While he says he is not as efficient as someone who has been in the trade for 15 years, he expects to make forty grand in the first year and eventually be able to bring his wife in to manage the business. He plans to open a cabinet shop in the basement of the building he is in, hire more craftsmen and grow the business until it covers the bills and retirement savings and then he can work exclusively on the elaborate projects that appeal to his creativity.

Ota has a different theory of why fewer kids want to enter the trades than people usually express. He says, “When you and I were kids and we had to write a report, we went to the library, and started looking for source material, and we sorted through a lot of resources, making copies and notes and reading books or pieces of them. Now kids just type the subject into Google and everything is right there.”

He is not saying that everything in life comes easy to kids today; he thinks some things make life harder like cyber bullying. However, he believes that with so much instant gratification and kids seeing people making lots of money by being influencers, kids develop less work ethic. In his experience, if you enlist kids to work, they stand around waiting to be told what to do instead of trying to pitch in.

Ota believes the only way to combat this thinking is to meet kids where they are, on TikTok for instance. They need to see people who are successful in trades roles and how interesting and fulfilling these roles can be. RB