Fire Codes are complicated.

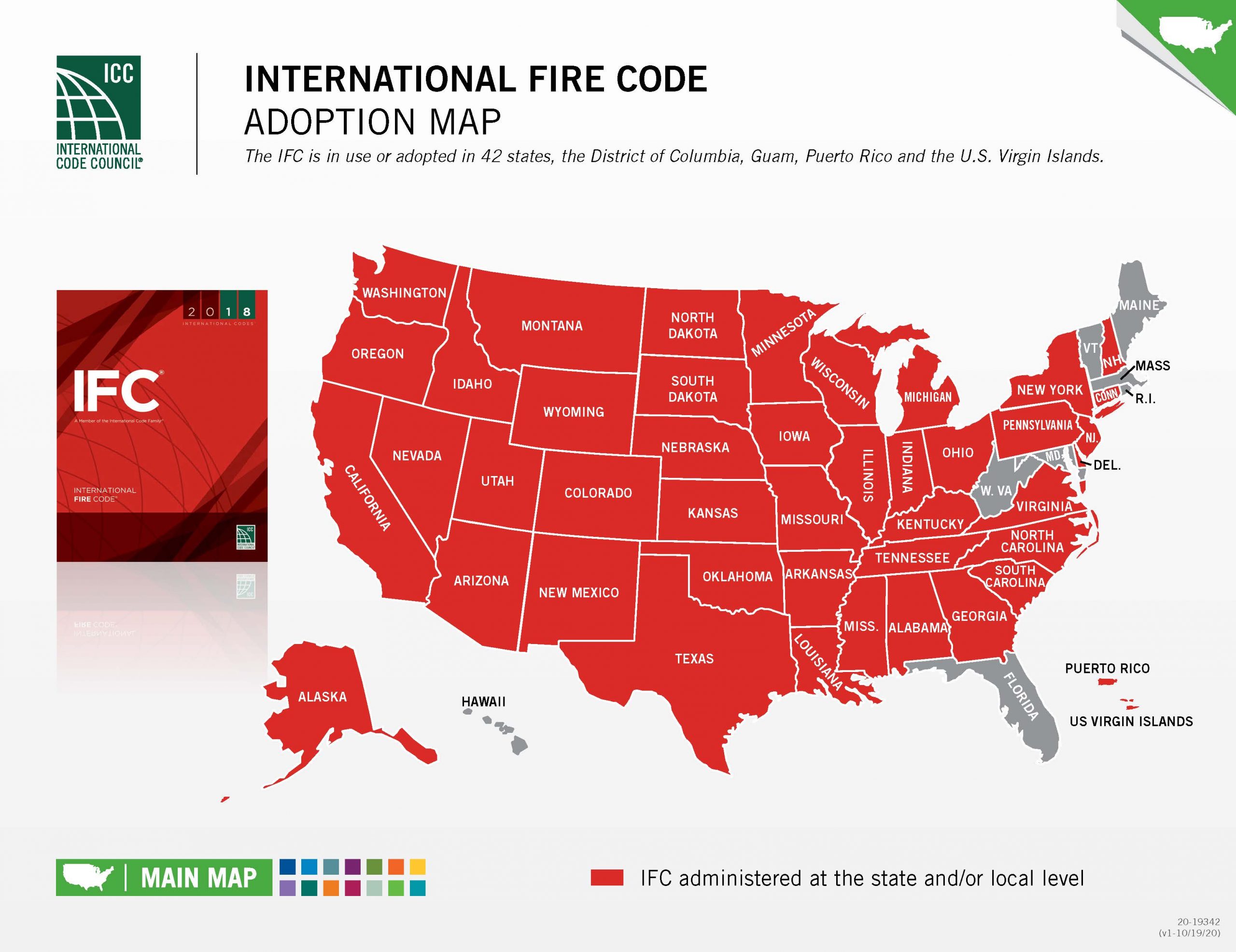

Most codes and standards are adopted from a few top national and international agencies like the National Fire Protection Association (NFPA) and the International Code Council (ICC). However, there is no mandate requiring states adopt these codes in full or at all. Counties and municipalities then have the power to implement and enforce these codes as they see fit. So, knowing what is current and enforced in your jurisdiction can be a challenge.

The codes represent minimum requirements to maintain public safety, but that baseline can understandably change depending on local environments. California, where wildfires are a constant threat, has more restrictions on combustible roofing and siding materials than Minnesota, where there is snow on the ground for half of the year.

Of course, striking a balance between fire-safe and cost-effective will always be a consideration for both the builder and the buyer. “Fire resistant materials are not something that they seek out because it’s often an added cost, but what they do want to do is find an economical way to add fire protection,” says Scott Johnson, technical representative for Louisiana-Pacific (LP) Building Solutions.

No matter where you are, you can assume that fire codes will only become more restrictive as time goes on, not loosen up. Changes in research, technology, the environment, and consumer demand all bring about alterations in the fire codes. In an effort to keep new projects “up to code” for as long as possible, it is beneficial for construction professionals to keep tabs on the newest evolutions in fire safety.

Know Your Codes

Imagining all of the ways your building project could be razed to the ground or all of the standards you should be following to prevent disaster is a baffling task. And while it’s all written out in the fire code, it can be valuable to have the ear of the local or state fire prevention expert for when you need clarification.

Ideally, you could look up your local fire inspector in the phone book, but state governments have delegated fire safety to many different departments, so it could take a little digging. In Wisconsin for example, the state fire marshal works primarily on arson cases with the Department of Justice while fire inspections are conducted by the Department of Safety and Professional Services in conjunction with local fire departments.

A good place to start is your local fire department. Even if they are not responsible for inspecting buildings in your area, they will more than likely have a relationship with the department or private contractor who does.

Jerry Deuman is the fire chief of the Waupaca Fire Department, just a couple of miles from the Shield Wall Media offices. They have more than 10 state-certified inspectors in the part-time fire crew who are available to consult on new construction and remodeling jobs. According to Deuman, they can be helpful for fire hydrant placement and other code questions before construction starts or to point out questionable aspects of an existing structure. “Just like building codes,” says Deuman, “fire codes are changing constantly. To keep up you almost gotta know somebody who really knows what they’re talking about.”

Some states work through the Highway Patrol, the Department of Natural Resources, the Department of Agriculture, or don’t conduct fire inspections at all.

Robert Kiser is a Fire Prevention Coordinator for the State of Wisconsin. His role is to consult with local fire inspectors and assist with enforcement of codes when disputes arise. In his position, Kiser works with fire inspectors of all levels, from part-time volunteers to fire prevention engineers. “Sometimes,” says Kiser, “it’s just the last guy in the building.”

Ideally, even if the local inspector is an amateur, there will be a person or team of people at the state level whose job is to know and enforce the codes. Even seasoned inspectors will sometimes call Kiser for clarification or to discuss more technical issues. “It’s all about safety,” says Kiser. That can be the safety of employees, livestock, property, or the public. “In Wisconsin I think we do it right,” says Kiser. “It gets someone from the fire department into local buildings. Then we can talk about the things we observe at drill night.” And the more people who understand how to apply the codes in many situations, the safer construction can be.

Know Your Environment

Are there external factors that cause a lot of structure fires in your area? Wildfires, floods, windstorms, tornadoes, and excessive lightning can all spark disaster. Climates prone to severe weather often already have regulations governing the use of combustible and fire-resistant building materials written into their codes.

More frequent and more severe storms and fires are a grim reality in many parts of the country and fire-prevention officials and consumers are taking notice. Adjusting your building materials to the environment can help keep you in line with changing building codes while creating consumer confidence and peace of mind. Anyone who has seen a photo with a single house standing in the middle of ash and rubble will want to replicate that success.

Many areas where wildfires and population density become dangerous, now classified as Wildland Urban Interface zones (WUI), require Class-A or (rarely) non-combustible materials in new construction. Mike Maddern, Director of Marketing and Sales at Arcitell®, points out the need for more WUI-compliant materials, “It’s proximity and flame spread that are driving the market. You don’t want a product that is going to easily spread fire between buildings.” He continues, “There are some restrictions particularly in Northern California that require exterior cladding to be non-combustible…but those areas are the exception, not the rule.”

Look for codes concerning Class-A rated roofing and siding materials, the addition of fire-retardant coatings, the distance between buildings, and even avoiding design elements like raised decks and eaves that can all trap heat in a fire scenario. “You want to take precautions,” says Johnson, of LP. “There are all sorts of things to consider. A lot of it comes down to luck; building materials are just one component of it.”

Other locations with fewer environmental risks may focus more keenly on controlling a fire that starts inside or safely evacuating a burning structure: fire walls and partitions, sprinkler systems, emergency lighting, and building assemblies with longer burn ratings that postpone structural collapse. Johnson noted, “There are specified times, one- or two-hour wall assemblies, depending on the type of structure and the overall goals of the codes. Either they are trying to protect from damage down to the studs, such as in a wildfire event, or trying to prevent collapse to safely evacuate the building.”

Development of fire-retardant materials has placed some choice back in the hands of the builder. In projects where environment would have once necessitated stone, brick, or other non-combustibles, there are plenty of options to suit various styles, budgets, and applications.

Know the Technology

As demand grows, more manufacturers are developing new or pushing their current fire-retardant materials. Products geared toward fire safety will generally be rated by flame spread (Class A–C) and a resistance rating.

Flame spread concerns how far flames will travel over the surface of a material in an allotted time compared to other, base materials. The lower the number, the slower it’s going to burn. A resistance rating is the time that materials or assemblies have withstood a standard fire exposure test. This rating can range from 10 minutes to several hours.

While these ratings are often more reliable as a ranked comparison of the products than an exact time marker, they are a great indicator to contractors concerned with fire safety.

When considering the outside of a structure the obvious non-combustible materials like brick and stone are always a good choice, but the associative costs of labor, transport, and time can be prohibitive to consumers. Arcitell, the developers of Qora® Cladding, wanted to fill the market gap with a realistic looking resin-based product that was easy to install and fire resistant.

“If we weren’t solving both of those problems,” says Maddern, “there would be no reason for us to come to market.” The resulting cladding is rated for Class-A applications, including zero lot line applications, and is less labor intensive to install. There is no reason to fear spreading fire with Qora cladding. “We have a flame spread index of zero, which means they couldn’t establish a flame to travel across the surface,” says Maddern.

If the customer is really set on wood siding, go with lumber pressure-treated with fire-retardant chemicals and rated for outdoor use. Hoover Treated Wood Products, Inc. began their business in fire-retardant-treated wood (FRTW) in 1955. A couple of decades later, they developed an exterior application for cedar shakes and shingles, which has now transitioned to plywood, dimensional lumber, trusses, and more under their Pyro-Guard® and Exterior Fire-X® brands.

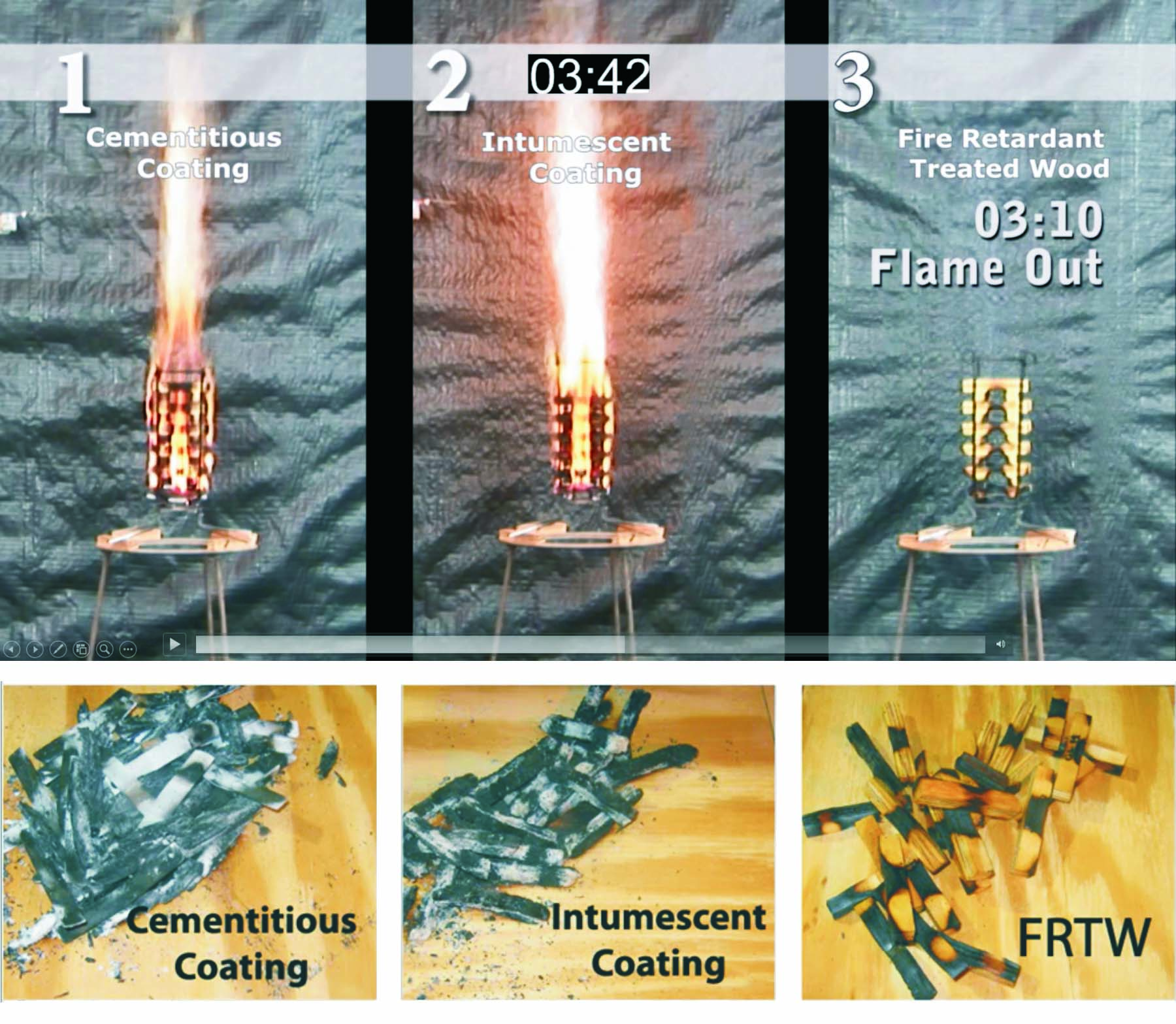

FRTW has been in use for more than 100 years, especially in military applications. Dave Bueche, Ph.D. explains “It works by fundamentally changing the way in which the wood burns.” Bueche pointed to Hoover’s FRTW Design and Construction Guide for an explanation: “Impregnation of wood with fire-retardant chemicals reduces the combustible properties of wood… FRTW is self-extinguishing and ignition resistant, resulting in no flaming, glowing, or smoldering combustion after the primary source of external fuel is exhausted.”

Along with siding, Exterior Fire-X® can provide a safe solution for wood decks, balconies, and trellises that are particularly large fire hazards.

Under the Roofing

One layer down in the building envelope, LP Building Solutions has created a fire-resistant sheathing for under any exterior cladding or roofing. FlameBlock® is standard OSB which is then coated on one or both sides with a non-combustible slurry that dries and strengthens the board.

Johnson explained the benefits of fire-resistant sheathing: “You have to think about what you’re trying to protect. In a wildfire, you are going to anticipate damage, but you want to limit that damage as much as possible. After a wildfire event the hope is to limit repairs to replacing the siding and sheathing instead of replacing a whole structure.”

On site, FlameBlock installs the same as regular OSB. The coating makes it slightly heavier, but still lighter than exterior gypsum. It can also be more difficult to cut, but there are easy solutions. “You just have to be careful not to chip off the coating. Use a saw blade with more teeth and cut a little slower,” says Johnson.

Metal roofing has been an industry standard for fire-resistant roofing for years. Any metal roof is a great deterrent to fire from exterior threats like floating embers and direct flame contact.

Developments are now being made in laminated architectural shingles that provide critical protection in a roofing assembly without sacrificing a more traditional style. Alex Pecora, Director of Product Management, Residential Roofing, with CertainTeed says, “[some CertainTeed tiles] include two layers of laminate for additional strength and can mimic the look of organic materials such as wood shake.”

Strides are also being made in long-lasting, environmentally safe coatings for flammable roofing and siding materials and the surrounding property. Take into consideration the codes and the environment where you live and work and explore what fire precautions make sense. As restrictions tighten across the country, the market will respond with greater and more cost-effective solutions you can incorporate into your projects.

Fire can cause devastating losses in a community, so maybe it’s best to work on the safe side. Even with the fire-retardant technology available to modern contractors, fire officials say it’s neglecting everyday maintenance—outdated fire extinguishers, dead fire and CO alarms, blocked exits—that does the most damage. “It’s the simple stuff,” says Chief Deuman. “You look at it every day, but you don’t think about it until it’s too late.” RB