What is Shou Sugi Ban, you may ask. The 2022 Source Book’s very first project (page 6) featured a shou sugi ban sided home, from John Nevadomski of Pioneer Millworks, and what a beauty it was! (See above.) Shou sugi ban is Japanese for “burnt cedar board.” It is believed that originally shou sugi ban was made from driftwood, sun and salt dried wood which was charred to create a fire-, rot-, and insect-resistant piece of wood.

Why Shou Sugi Ban?

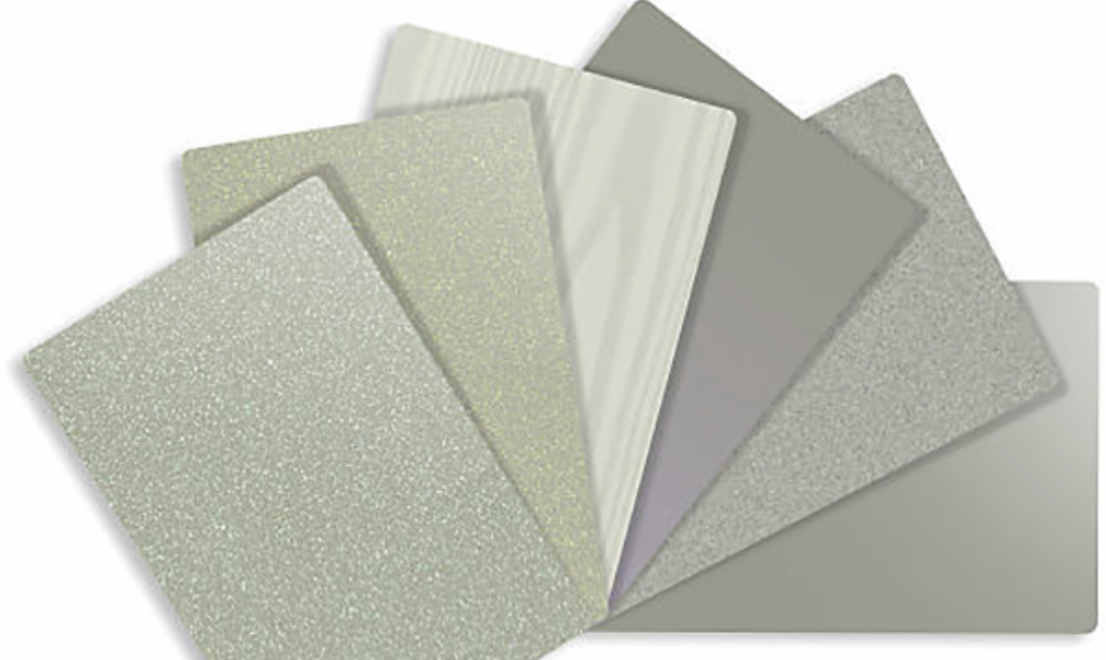

Today, many people choose shou sugi ban siding because they find the aesthetic appealing. Contemporary design trends have moved toward more natural choices with rich visuals. The wood is burnt to create a lignin layer which may or may not be brushed away, depending on preference, to reveal an enhanced natural grain, toasted tones wood grain, or a jet-black carbon tone. The effect depends on the length of time the wood is left to burn. Some shou sugi ban is also color treated for a unique look.

Since the wood is generally only burned to approximately 1/16 of an inch, the insect-, fire-, and rot-resistant properties acquired by burning are minimal. However, a top coat is applied to the wood to enhance those effects.

If a customer is interested in building “green,” shou sugi ban is a viable choice. As a piece of wood, it is inherently sustainable, acting as a carbon sink, requiring less energy to create than many other materials like steel or concrete, and of course, it is renewable.

The process of shou sugi ban does not add toxicity to the product or the environment and the products can be treated with a Zero VOC finish.

How is Shou Sugi Ban created?

Common wood choices for shou sugi ban are larch, cedar, pine, spruce, Douglas fir, Accoya®, and oak. Nevadomski says that Pioneer Millworks offers larch, Douglas fir, and Accoya. Larch and Douglas fir are naturally unappealing to insects, and Accoya has no sugar left to nourish pests after treatment, so it is especially insect resistant.

There are different methods of burning the wood, from setting it up outdoors in a teepee-type shape and applying fire to it by hand in the traditional manner to mechanized processes. Nevadomski says they have modern production equipment with a chamber that focuses the heat allowing them to burn more wood in an efficient and consistent manner.

How is Shou Sugi Ban Maintained?

Shou sugi ban is a wonderful example of the Japanese concept of wabi sabi, finding beauty in the imperfect and the impermanence of nature. The looks of shou sugi ban will weather and change over time, fading back to the original patina of the wood. However, the wood can be refinished to maintain its unique look.

The History of Shou Sugi Ban

By Megan Avila, Pioneer Millworks

Shou sugi ban charred wood originated in Japan. A cursory Google search will show varying claims for the date of origin, but the focus is usually on shou sugi ban’s extraordinary longevity. One hurdle to research is language. English-speakers know this charred wood as shou sugi ban, but in Japan it’s called yakisugi, yakisugi-ita, or yakiita.

Researchers from the University of Tokyo found that the earliest written record of the word “yakisugi” is from a dictionary published in only 1930. Centuries-old structures clad in charred wood and oral tradition dating back to the Edo period (1603-1867) is compelling evidence that “yakisugi” is a fairly new term. If shou sugi ban was known by other names in the past, those older names may be lost to antiquity.

Prior to 1970, shou sugi ban had a reputation as a poor man’s building material installed on storehouses in industrial zones and on residences in areas not easily visible to passersby. Today, shou sugi ban is being used in high-end, modern spaces.

Our research suggests that shou sugi ban was developed sometime between 1603 and 1868, during the Edo period. It was during this time of unification that Japan experienced a huge population boom and a new, rigid social stratification system was put in place. By the 1750s, Edo was likely the most populous city in the world. The bottom rung of the social ladder was the merchant class, a populous group in the dense urban center of Edo. They built and occupied machiya, traditional wooden townhouses, and stored their goods in warehouses known as kura.

Aside from being the new center of political power and the cultural mecca of Japan, the dense urban center of Edo was ripe with these traditional wooden townhouses. Susceptible to tragedy of flame, nearly 1,800 fires were recorded during this period—destroying countless structures and killing thousands of people.

It is not hard to imagine that using a fire-resistant material was a priority, especially among those that couldn’t afford to build with stone or stucco. Enter shou sugi ban. By the end of the Edo period, many of the merchant class had amassed considerable wealth and status despite the rigid class system imposed on them. The shou sugi ban on their warehouses protected their goods, and on their homes it protected their families.

The charred wood that protected those structures waned in popularity as the populace began to favor new materials and pre-existing technologies became more affordable. Shou sugi ban regained popularity in Japan in the 1970s, giving rise to mills specializing in large-scale manufacture of shou sugi ban. Architects like Yoshifumi Nakamura are internationally known for projects featuring charred wood, and have bolstered its popularity by holding special exhibitions and workshops around the world demonstrating traditional manufacturing techniques and experimenting with different wood species. Architect Terunobu Fujimori is featured in a number of YouTube videos speaking about the more traditional aspects of manufacturing shou sugi ban (yakisugi).

Shou sugi ban is often made with more modern and efficient techniques today, but they are based on the traditional lessons taught by Fujimori et al. One of them is that many woods are suitable for burning. Pioneer Millworks uses sustainable Larch, Douglas fir, and modified wood like Accoya®, depending upon the project needs and client wishes.

We’ve been fascinated by charred wood for its look and texture plus its resistance to rot, insects, and fire. Moving beyond the traditional “alligator” char, we’ve developed new surfaces and tones.

Enhancing the grain, adding a pop of color or a strong neutral, there is nothing quite like charred wood. Call it shou sugi ban, yakisugi, or yakiita—this technique remains relevant and celebrated centuries after its introduction.

RB